Jimi Famurewa Reflects on His Culinary Journey and Cultural Identity

To grasp my early aversion to certain foods — my transition from a picky eater to a devoted food enthusiast — one pivotal experience stands out: the jollof rice incident. It was 1995, and I was a fresh-faced secondary school student in Bexleyheath, navigating the complexities of a new community as a British-Nigerian teen in the bustling halls of a large comprehensive school in southeast London.

As I recall, my tutor group lined up to enter a classroom when a classmate, let’s call her Sabrina, notorious for her teasing, turned to me with a smirk. “Is it true,” she exclaimed loudly for everyone to hear, “that Africans eat bright orange rice?” Her exaggerated disgust drew the other students’ attention, akin to a courtroom drama.

I instantly pictured the vibrant, spiced mounds of jollof rice my mother prepared weekly. I remembered family gatherings filled with cool boxes brimming with the dish, glowing with color like a cinematic artifact. In that moment, the pressure to conform and the hunger to fit in, particularly as an immigrant’s child, felt insurmountable. “Uh, w-what?” I awkwardly responded, “No, of course we don’t!” In that instant, I betrayed my culinary heritage, believing it would help me distance myself from anything perceived as ‘different’ or ‘strange’.

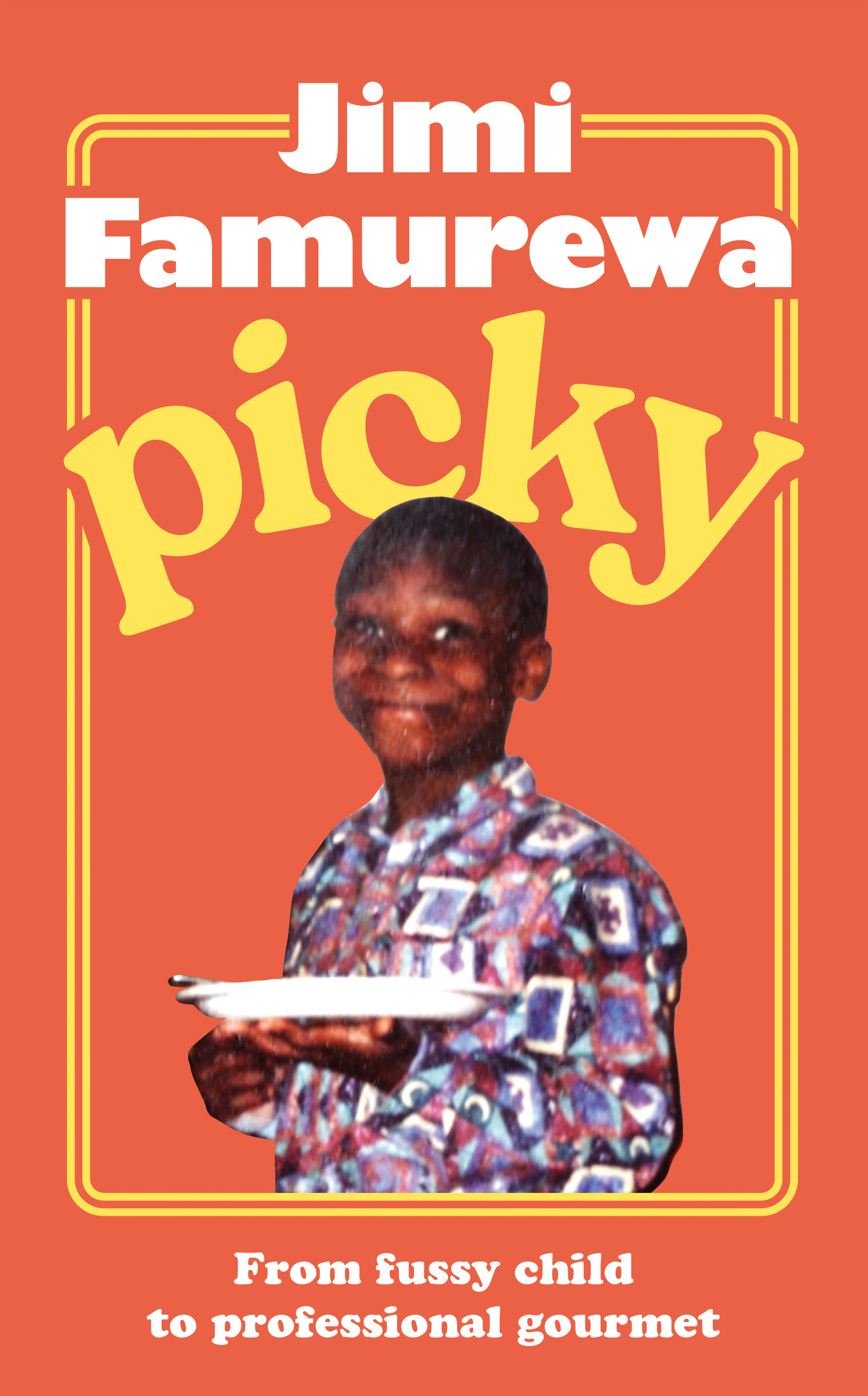

This early encounter encapsulates a significant theme in my memoir, Picky, which traces my evolution from a selective eater to an esteemed restaurant critic and MasterChef judge. Throughout my time in a predominantly white school, open ridicule regarding Nigerian cuisine was uncommon for me, but this incident was telling of the social dynamics of that time. Interestingly, Sabrina, despite her Caribbean background, was also black, adding complexity to my experience. Yet, this singular event highlights the social landscape of my youth and its lasting impact on my identity.

This era was defined by targeted jeers about “exotic” or “unusual” foods that strayed from societal norms. In primary school, I recall a red-haired girl facing relentless teasing for her beetroot lunch, rumored to carry an unspecific contagion. Meanwhile, South Asian peers dealt with unpleasant jokes about the scent of curry wafting from their lunchboxes.

The anxiety tied to traditional foods — sometimes termed the “lunchbox moment” — is a recognizable experience among second-generation immigrants, often shaping their childhood narratives. In a 2020 interview, BBC presenter Naga Munchetty shared how her Indian mother insisted her children change out of their uniforms to avoid being labeled as the Asian kids who smelled of curry. Similarly, Angela Hui’s memoir, Takeaway, reveals her struggle with racist prank calls and feeling different due to her family’s food business. Many children of diverse backgrounds find their culinary identities become a battleground.

Aside from the Sabrina incident, I didn’t face much overt hostility; however, my intense reluctance towards unfamiliar foods and embarrassment about fresh fruits boiled over, making me keenly aware of how my dietary habits could further ostracize me. This consciousness led me to absorb the stigma associated with the “foreign” foods I had once enjoyed, especially when separated from the comforting embrace of my family’s home. This encounter wasn’t merely about denying my heritage; it represented a split between my identity and tastes established early in my childhood.

My parents embodied a typical Nigerian practicality regarding their children’s identity in Britain. Both hailing from postwar Nigeria, they represented a post-colonial generation of immigrants eager for their offspring to thrive through adaptation. My older brothers attended private schools, while I insistent on enrolling in a state school. Later, we relocated to a neighborhood where we were notably one of only two black families along the lengthy street. My parents attempted assimilation by giving me the “English” name Roger in an environment filled with Garys and Chris’s, hoping it would help me fit in seamlessly.

My mother, a proud Nigerian, raised us in line with her cultural values (my father lived in Lagos and was less involved). She often spoke Yoruba at home, donning traditional attire for family gatherings, insisting we embrace our African identity despite our life in the UK. She created a protective barrier of pride and identity that buffered us from the sting of racial insults. Yet, it may not have prepared her for the psychological turmoil of navigating multiple cultural identities as an adolescent.

In my quest to avoid exclusion because of my racial and cultural background, I rejected much of the rich diversity inherent in Nigerian cuisine and found allure in fast food and snacks, convincing myself I disliked dishes like curry without ever sampling them.

So, what catalyzed my transformation? How did I move past my culinary fears? My transition unfolded gradually rather than through a singular epiphany. Attending university, filled with diverse dining experiences and a delightful summer journey through France, expanded my palate. The early 20s saw me delve into cooking, much like countless aspiring chefs; I discovered a world of flavors I had long shunned, diving into it with a fervent passion.

By the time I entered the food media realm in 2018, first with a restaurant column, then as a critic on MasterChef, my journey had come full circle. A significant moment came in 2010 when I visited Nigeria as an adult, savoring barbecued suya from newspapers — a joyous reconnection with my culinary roots that I had once fled.

A notable highlight of my journey occurred during a 2023 Christmas special of MasterChef, where I had the chance to prepare a dish of my choice. I instinctively chose jollof rice, the very meal I once distanced myself from. While my cooking attempt was chaotic and somewhat underwhelming, the act of representing my heritage on a prominent platform symbolized my full circle journey. Once a target of ridicule, jollof rice now stands as a celebrated symbol of West African cuisine, featured in Michelin-starred restaurants across London. It seems both jollof rice and I have traversed a significant journey.

Picky, written by Jimi Famurewa and published by Hodder & Stoughton, delves into his unique experiences with food and identity.

Jollof Rice Recipe by Kofo Famurewa

Ingredients

• 800g tinned plum tomatoes • 1 red bell pepper • 1 red pointed pepper • 1 thumb-sized piece of fresh ginger • 3 medium onions • 1 scotch bonnet pepper • 4 cloves of fresh garlic • 50ml sunflower or vegetable oil • 1 tbsp curry powder • 1 stock or flavoring cube (Maggi is preferred) • 1 tbsp tomato purée • 2 bay leaves • 500g easy-cook basmati rice • 500ml chicken or vegetable stock • 1 knob of butter or plant-based spread • Salt and black pepper • Kitchen foil

Method

1. Blend the tomatoes, peppers, ginger, two onions, the scotch bonnet (using half for milder heat) and garlic to create a smooth mixture. Warm oil in a large saucepan; chop and sauté the remaining onion for 5-10 minutes.

2. Add the blended mixture to the pan and cook over medium heat until oil separates (about 20 minutes), stirring occasionally. Incorporate generous amounts of salt, pepper, curry powder, crumbled flavor cube, tomato purée, and bay leaves. Continue cooking down for an additional 5 minutes, checking seasoning as desired, and remove from heat.

3. Rinse the rice in a strainer under running water until the water is clear.

4. Combine rice with the sauce in the saucepan and stir until well-coated. Lower the heat to very low, covering the pan tightly with foil and placing the lid on top. Simmer, stirring occasionally, to avoid sticking.

5. Cook until liquid is absorbed, then add stock and stir. Cover tightly to catch steam and leave on low heat for 50-60 minutes until rice is cooked and fluffy. Finish with a knob of butter or plant-based spread.

Post Comment